Note: This post requires some basic knowledge of vector and differential calculus.

Variable mass system dynamics

The principles that govern the dynamics of rockets are the ubiquitous Newton’s laws. However, to analyze a rocket we must take into account that we are dealing with a variable mass system. So the classical expression \(\sum_{i} \vec{\mathbf{f}}_i = m \vec{\mathbf{a}}\) is not valid in this case. Specifically, we need to use Newton’s second law in its original form, which states that the rate of change of momentum of a body is directly proportional to the force applied, and this change in momentum takes place in the direction of the applied force. Basically, Newton’s second law can be formulated as

\[\sum_{i} \vec{\mathbf{f}}_i = \frac{d \vec{\mathbf{p}}}{dt}\]where \(\vec{\mathbf{p}}\) is the linear momentum vector, defined as he mass of the system times its velocity \(\vec{\mathbf{p}} = m \vec{\mathbf{v}}\). Before applying the equation, we need to determine what forces act on the rocket and what is the net exchange of linear momentum between two infinitesimal time instances.

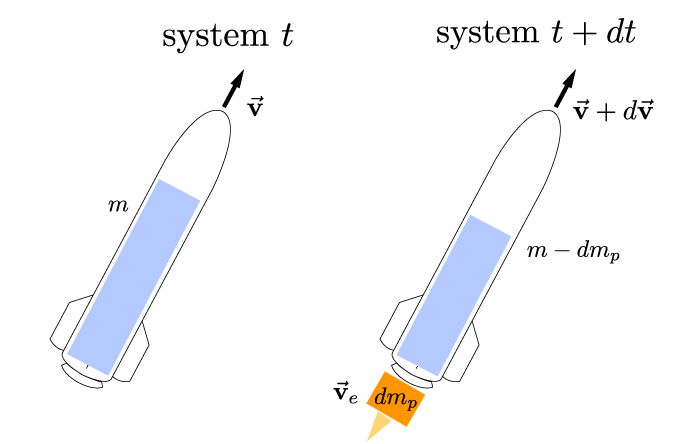

Let the mass of the rocket at time \(t\) be \(m(t) = m_s + m_p(t)\), where \(m_s\) and \(m_p(t)\) are the dry mass of the rocket (assumed to be constant) and \(m_p(t)\) is the propellant mass (or wet mass) which varies in time as it is consumed through combustion. Also at time \(t\), the velocity of the rocket is \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\). We assume that between the two infinitesimal time instances the exhaust velocity of the combusted propellant relative to the rocket \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}_e\) is constant. Thus, the momentum of the rocket and propellant system at time \(t\) is

\(\vec{\mathbf{p}}(t) = m\vec{\mathbf{v}}\).

After \(dt\) time units, the velocity of the rocket has changed infinitesimally to \(\vec{\mathbf{v}} + d\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) and its mass is \(m - dm_p\) since some of the propellant mass has been expelled. Hence, the momentum of the rocket is \((m - dm_p)(\vec{\mathbf{v}} + d\vec{\mathbf{v}})\). We must not forget that the expelled propellant also contributes to the momentum at time \(t + dt\). Specifically, its momentum is the mass times the velocity of the expelled propellant \(dm_p(t)\vec{\mathbf{v}}_{dm_p}\). Here, we used the fact that the velocity of the expelled mass must be expressed in an inertial frame and that the expelled mass velocity relative to the rocket is \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}_e = \vec{\mathbf{v}}_{dm_p} - (\vec{\mathbf{v}} + d\vec{\mathbf{v}})\), where \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}_{dm_p}\) is the absolute velocity of the expelled mass. The momentum of the combined rocket and propellant system at time \(t + dt\) is then

\(\vec{\mathbf{p}}(t + dt) = (m - dm_p)(\vec{\mathbf{v}} + d\vec{\mathbf{v}}) + dm_p(\vec{\mathbf{v}}+ d\vec{\mathbf{v}} + \vec{\mathbf{v}}_e)\).

After neglecting second-order infinitesimal terms, the change in momentum between two infinitesimal instances at \(t\) and \(t + dt\) finally yields

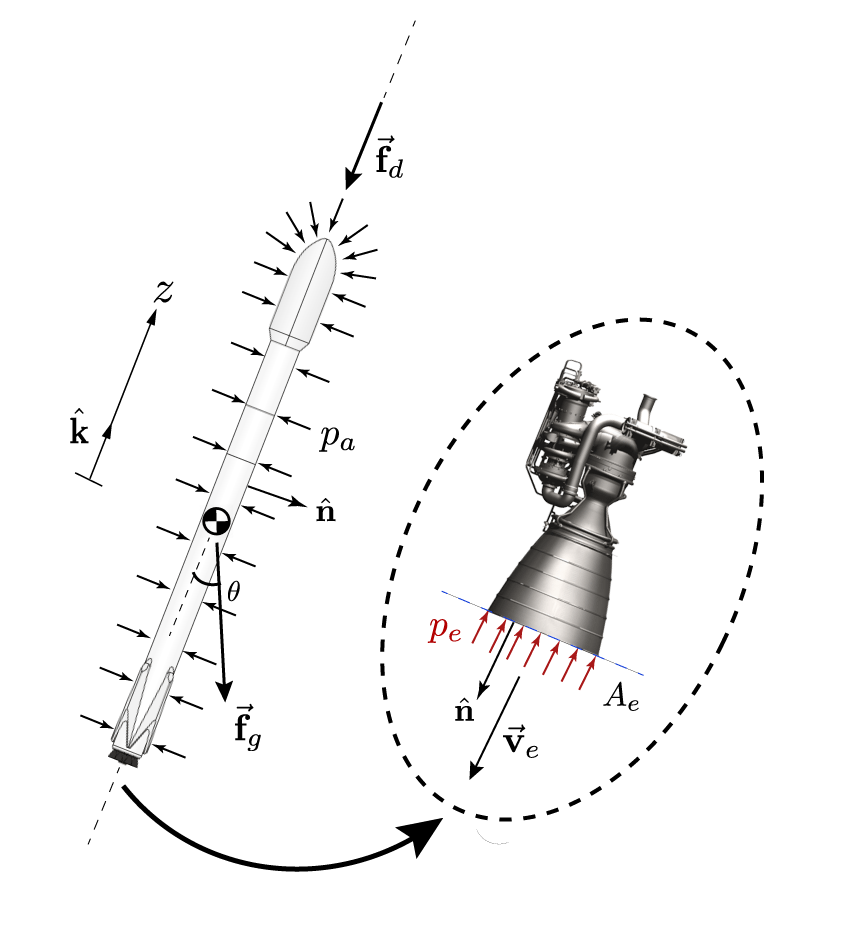

\[d\vec{\mathbf{p}} = m\,d\vec{\mathbf{v}} + dm_p\,\vec{\mathbf{v}}_e\]Now, let us examine the external forces acting on the rocket. The predominant forces are the force due to gravity, net pressure force and atmospheric drag as sketched in Figure 2.

The principal force that the rocket must overcome to get into space is the force due to gravity, which is expressed as \(\vec{\mathbf{f}}_g = m \vec{\mathbf{g}}\). This force is the responsible for keeping the rocket on the Earth’s surface, maintaining its state at a minimum potential energy. The air molecules of the Earth’s atmosphere exhert a static pressure on the rocket surface given by \(p_a\). In this case, we assume that the atmospheric pressure is constant around the vehicle. The net pressure force is the surface integral of the local pressure acting on a differential surface area, given by

\[\vec{\mathbf{f}}_p = \int_{A}p_s\,\hat{\mathbf{n}}dA\]The resultant static pressure force around the rocket is different from zero due to the pressure difference between the high energy exhaust gas and the atmospheric pressure. If there was no pressure difference, the total net static pressure force on the rocket would be zero. The surface integral reduces to

\[\vec{\mathbf{f}}_p = \int_{A}p_s\,\hat{\mathbf{n}}dA = (p_e - p_a)A_e \hat{\mathbf{k}}\]Now, we assume that pressure acts uniformly accross the differential areas and \(A_e\) is the exhaust or exit area.

The aerodynamic drag force is the resultant force due to air resistance when the rocket flies around the Earth’s atmosphere. Usually, the atmospheric drag force is a function of the atmospheric density, relative velocity between the rocket and sorounding air and the cross sectional area of the rocket \(A_c\) weighted by a form factor \(C_d\). Typically, one would assume the well-known quadratic velocity dependence \(\vec{\mathbf{f}}_d = -\frac{1}{2}\rho (\vec{\mathbf{v}} \cdot \vec{\mathbf{v}}) \hat{\mathbf{v}} A_c C_d\) (here \(\hat{\mathbf{v}} = \hat{\mathbf{k}}\)). However, this expression is only valid for certain velocity regimes and when the atmospheric density can be modeled as a macroscopic quantity (low Knudsen numbers). Since a rocket operates from the Earth’s surface to space and at sub-, super- and hyper-sonic regimes, the drag force gets really complicated to model. In fact, for hypersonic regimes the drag force is proportional to the cubic velocity, and heat transfer effects become relevant. So, we will call the magnitude of the drag force simply \(D\) directed in the opposite direction of the rocket’s relative velocity.

To make things simple, we will project the equations onto the z reference frame, aligned with the rocket’s direction of flight. The projected forces onto the z-axis yields (note the sign conventions according to Figure 2)

\[f_z = - m g \cos (\theta) - D + (p_e - p_a)A_e\]and the infinitesimal change in momentum yields

\[\frac{d p_z}{dt} = m\,\frac{d v}{dt} - \frac{d m_p}{dt}\,v_e\]Conservation of mass tells us that the expelled propellant contributes to a reduction of the rocket mass at a rate \(\frac{d m}{dt} = -\frac{d m_p}{dt} = -\dot{m}_p\). Plugging this relation in the projected momentum equation and equating it to the external forces gives

\[m\,\frac{d v}{dt} + \frac{d m}{dt}\,v_e = - m g \cos (\theta) - D + (p_e - p_a)A_e\]Depending on the assumptions, we can distinguish different cases for the rocket equation:

Case 1: No external forces

In the idealized case where we assume no gravity and drag forces on the rocket, the dynamics equation yields

\[m\,\frac{d v}{dt} = \dot{m}_p\,v_e + (p_e - p_a)A_e\]Comparing the above equation to the classical Newton’s second law, we observe that the left hand side term corresponds to the inertial term whereas the right hand side term must be a force. This force is the thrust \(T\) that the rocket generates due to combustion and expelled mass. The rocket thrust equation is given by

\[T = \dot{m}_p\,v_e + (p_e - p_a)A_e\]We can see that thrust contains to terms. The term \(\dot{m}_pv_e\) is often called momentum or jet thrust due to change in momentum, and the term \((p_e - p_a)A_e\) is known as pressure thrust due to a pressure difference at the nozzle exit. Thus, thrust depends on the mass flow rate ejected, the exhaust velocity and the exit pressure. These quantities depend on the nozzle design. Aassuming isentropic flow the exhaust velocity \(v_e\) and exit pressure \(p_e\) are inversely proportional, that is, as one increases the other decreases. The maximum thrust \(T\) occurs when the exit pressure \(p_e\) equals the ambient pressure \(p_a\).

If we divide both sides of the dynamics equation, we obtain

\[\frac{m}{\dot{m}_p}\,\frac{d v}{dt} = v_e + \frac{(p_e - p_a)A_e}{\dot{m}_p}\]and we define \(c_e = v_e + \frac{(p_e - p_a)A_e}{\dot{m}_p}\) as the effective exhaust velocity. Conservation of mass tells us that the expelled propellant contributes to a reduction of the rocket mass at a rate \(\frac{d m}{dt} = -\frac{d m_p}{dt} = -\dot{m}_p\). Plugging this relation into the dynamics equation and using the definition of effective exhaust velocity yields

\[-\frac{m}{\frac{d m}{dt}}\,\frac{d v}{dt} = c_e\]Assuming that the exhaust velocity and mass flow rate are constant over the time of integration, integrating the above expression yields

\[\int_{v_0}^{v}\frac{d v}{dt}dt = - \int_{m_0}^{m}\frac{d m}{m}\,c_e\]which gives

\[\Delta v = v - v_0 = c_e\,\text{ln}\bigg(\frac{m_0}{m}\bigg)\]This equation relates the increment in velocity that a rocket can achieve, a fundamental property to reach specific orbits. This delta-v depeds on the ratio of initial and final mass and the exhaust velocity. Due to combustion, the internal energy of the propellant is transformed into kinetic energy, generating a momentum exchange that propels the rocket vehicle. If all the propellant is burned, the final mass is just the dry mass of the rocket, also called burnout mass. Then, the ratio between the initial and burnout masses is often calles the \(R\) ratio, and the delta-v is expressed as

\[\Delta v = c_e\,\text{ln}(R)\]Often, instead of expressing the delta-v interms of exhaust velocity, a more common choice is to use the relation \(c_e = I_{sp}g_0\) where \(I_{sp}\) is the specific impulse, a quantity that measures in seconds the efficiency of how the propellant is transformed into kinetic energy, and \(g_0 = 9.81 m/s^2\) the standard gravity constant. The rocket equation, also known as Tsiolkovsky rocket equation is then

\[\Delta v = I_{sp}\,g_0\,\,\text{ln}\bigg(\frac{m_0}{m}\bigg)\]Let’s move on to the second case, where we include gravity effects.

Case 2: Considering gravity effects

In this case, where we assume gravity is acting in the direction of the flight path, the dynamics equation reads

\[m\,\frac{d v}{dt} = - c_e\,\frac{d m}{dt} - mg\]and after integration and assuming that the acceleration of gravity is constant \(g = g_0\), yields

\[\Delta v = c_e\,\text{ln}\bigg(\frac{m_0}{m}\bigg) - g\,\Delta t\]or in terms of specific impulse

\[\Delta v = g_0\,\bigg[I_{sp}\,\,\text{ln}\bigg(\frac{m_0}{m}\bigg) - \Delta t\bigg]\]This expression tells us that gravity consumes part of \(\Delta v\), since the rocket has to consume energy to counteract the Earth’s gravity potential. The effect of loss in delta-v due to gravity is usually termed gravity loss. An important difference when we consider gravity is that the delta-v depends on the time of flight \(\Delta t\).

Case 3: Considering drag effects

If we additionally consider atmospheric drag effects, we obtain

\[m\,\frac{d v}{dt} = - c_e\,\frac{d m}{dt} - mg - D\]As explained above, drag depends on the atmospheric density, relative velocity of the rocket with respect to the sorounding air and geometry of the rocket. Drag models vary drastically depending on the velocity regime and height, which makes it very hard to model and is beyond the scope of this post. However, it is important to note that drag will also be responsible for a loss in delta-v since the kinetic energy will be lost due to heating and dissipative effects.

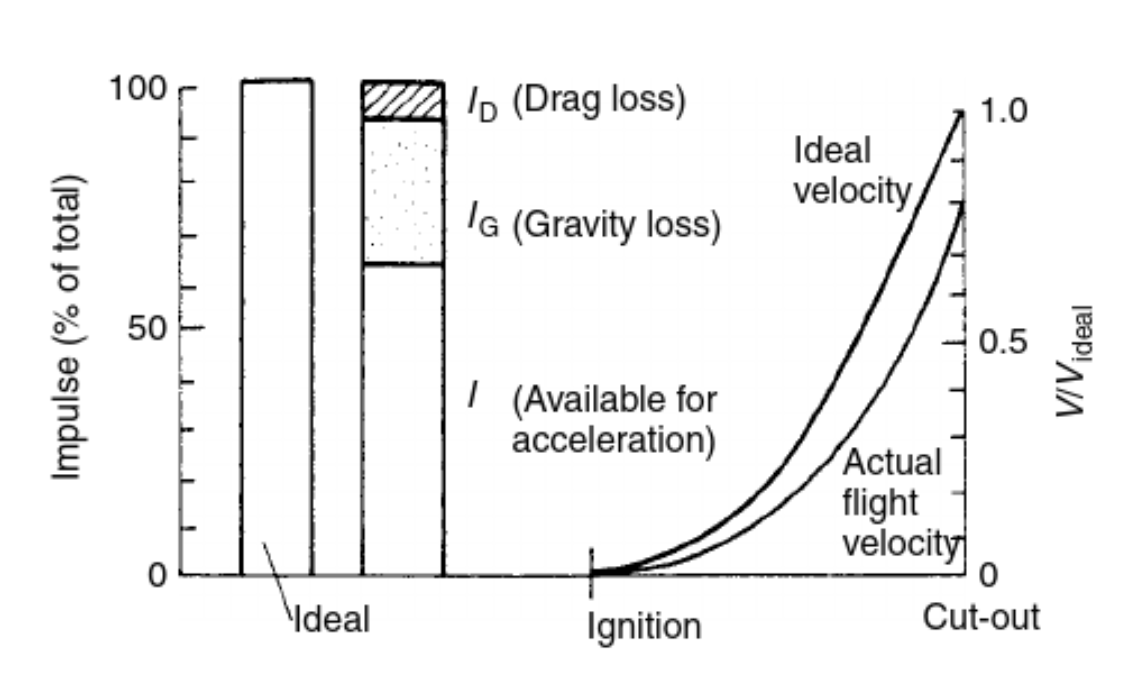

The general case for delta-v can be expressed as

\[\Delta v = \Delta v_{ideal} - \Delta v_g - \Delta v_d\]where

\[\Delta v_{ideal} = c_e\,\text{ln}\bigg(\frac{m_0}{m}\bigg)\] \[\Delta v_g = \int_{t_0}^{t} g \cos(\theta) dt\]and

\[\Delta v_d = \int_{t_0}^{t} \frac{D}{m} dt\]In this case, g is allowed to vary throughout the trajectory, and D is a function of the velocity, local atmospheric density and geometry of the rocket. The above expression makes clear the losses of delta-v due to gravity effects, where energy is required to counteract the gravity potential, and drag effects, where the air resistance dissipates the kinetic energy of the vehicle in the form of heat.

Figure 3 below compares the delta-v losses due to gravity and drag from the ideal case.

So, that is it for now! Another important concept to understand is how the mass flow rate, exhaust velocity and exit pressure depend on each other. That is a topic covered in noozle design, compressible and inestropic flow that hopefully I will cover in another post.

I hope you enjoyed this post! Thank you so much for reading!

Alex.

References

1) Curtis, Howard D. Orbital mechanics for engineering students. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2013.

2) J. Peraire, S. Widnall. Variable Mass Systems. 16.07 Dynamics, MIT Lecture Notes. Fall 2008.

3) M. Martinez-Sanchez, Unified Engineering Notes, Course 95-96.

4) Fortescue, Peter, Graham Swinerd, and John Stark, eds. Spacecraft systems engineering. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.