Note: This post requires some basic knowledge of linear algebra and vector calculus.

Introduction

I stumbled upon the realm of rotational dynamics when I was working on the attitude determination and control system of a small satellite a few years back. At first, it was a bit daunting because I had never worked in attitude dynamics before and I only had basic knowledge from my undergraduate courses. However, I started to learn from books and put everything in practice. Finally, I ended up loving this field, and I would like to do my bit by sharing one of the concepts that fascinates me: orientation (or attitude) and rotational dynamics of rigid bodies in three-dimensional space. Understanding and describing how an object is oriented in space is crucial for aerospace applications: from maneuvering aircraft and spacecraft to describe the attitude dynamics of asteroids or other orbiting bodies.

The motion of particles, bodies or system of bodies without considering the agents that cause them to move is often referred as kinematics. The motion of any body in a three-dimensional space can be described by six parameters, also known as degrees of freedom (dof) which are divided in three translational dofs and three rotational dofs. On the one hand, the “position” of a body is often described by the “x”, “y” and “z” Cartesian coordinates. On the other hand, the orientation or “attitude” of a body can be expressed by three different “angles”. However, these are not the only ways to describe position and attitude. The focus of this post is to explain the different representations one can use to describe the orientation of a body.

Notation: In this post I will refer to vectors as \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) where its components in a specific reference frame as the column matrix \(\mathbf{v}\). Vectors with unit norm will be written with a hat symbol \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\). For matrices, I will use a bold, uppercase letter \(\mathbf{A}\) if they are two dimensional and bold, lowercase letter \(\mathbf{a}\) if they are one dimensional (that is, column matrices).

The first step to describe the orientation of a body in space is to introduce the concept of reference frame. A frame of reference consists of a set of three orthogonal unit vectors (axes) \(\{\hat{\mathbf{e}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{e}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{e}}_3\}\) and an origin \(\mathcal{O}\) that fixes those axis to a certain location in space. If we wanted to describe the position of a body, we would use the set \(\{\mathbf{O},\hat{\mathbf{e}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{e}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{e}}_3\}\), but since we are interested in the orientation we will drop the origin and assume all vectors are referenced to it. The reference frame \(\mathcal{O}\) is then defined as \(\mathcal{O}:\{\hat{\mathbf{e}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{e}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{e}}_3\}\). Once the reference frame is defined, we can express any vector in that frame as

\[\vec{\mathbf{v}} = v_1\hat{\mathbf{e}}_1 + v_2\hat{\mathbf{e}}_2 + v_3\hat{\mathbf{e}}_3,\]where \(\{v_1, v_2, v_3\}_{\mathcal{O}}\) are the coordinates of \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) in the reference frame \(\mathcal{O}\). Note that the coordinates are the orthogonal projections of \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) onto each basis vector \(\hat{\mathbf{e}}_i\) (i.e. \(v_i = \vec{\mathbf{v}}\cdot\hat{\mathbf{e}}_i,\quad i = 1,2,3.\)).

To define the attitude of an object we must always have in mind that the orientation is a relative concept. One defines the orientation of an object relative to a reference frame. Thus we must employ two reference frames, one attached to the object and another one that will be used to describe the orientation with respect to it. Let’s define two reference frames defined by their orthogonal basis vectors as \(\mathcal{A}: \{\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\}\) and \(\mathcal{B}: \{\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{b}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\}\). The goal is to represent the attitude of \(\mathcal{B}\) relative to \(\mathcal{A}\). There are many attitude representations to achieve this goal. In this post I will focus on four of them: direction cosine matrix (DCM), axis-angle representation, Euler angles and quaternions.

Direction Cosine Matrix (DCM)

The direction cosine matrix is the most fundamental of all attitude representations and the one we will first study.

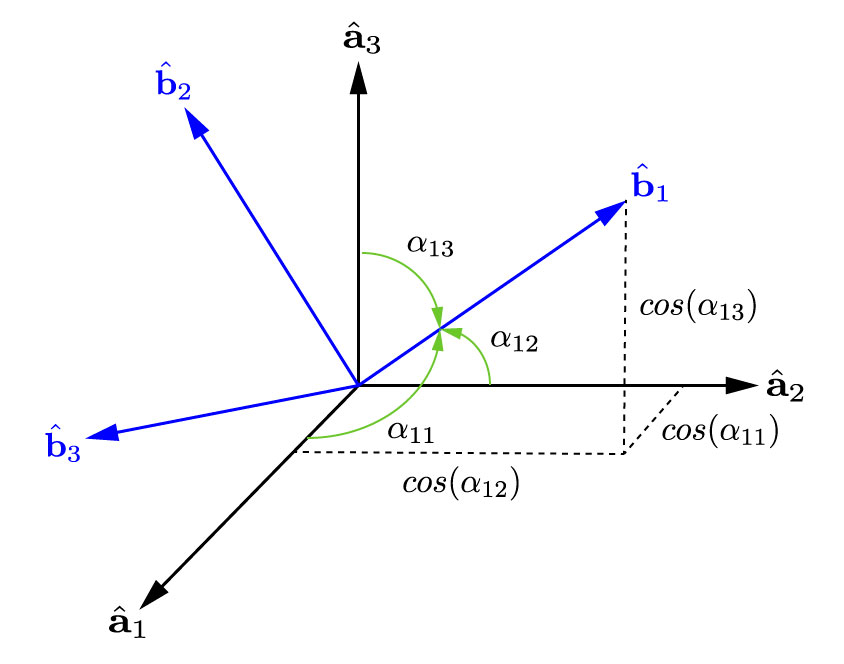

The direction cosine matrix allows us to express the basis vectors of one reference frame in terms of the basis vectors of a different one by means of the angles formed by them. We will call \(\alpha_{ij}\) the angle that goes from basis vector \(j\) of \(\mathcal{A}\) to basis vector \(i\) of \(\mathcal{B}\). Let’s start by expressing \(\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\) in terms of \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\). As discussed before, any vector can be expressed in a reference frame as

\[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1 = b_{11}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + b_{12}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + b_{13}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\]where each component \(b_{ij}\) is simply the orthogonal projection of \(\mathbf{b}_i\) onto each basis vector \(\mathbf{a}_j\). For the second component, for example, \(b_{12} = \hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 = \|\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\| \|\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\| \text{cos}(\alpha_{12})\). Since both \(\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\) have unit norm, the projection of \(\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\) onto \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\) is simply the cosine of the angle formed by the basis vectors. If we repeat this process for all basis vectors of \(\mathcal{B}\), we should obtain

\[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1 = \text{cos}(\alpha_{11})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{12})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{13})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\] \[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_2 = \text{cos}(\alpha_{21})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{22})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{23})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\] \[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_3 = \text{cos}(\alpha_{31})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{32})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{33})\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\]

For convenience, we can stack the basis vectors as rows of a matrix, called “vectrix”, and express the relations above as

\[\{\mathcal{B}\} = \begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\\\hat{\mathbf{b}}_2\\\hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\alpha_{11}) & \text{cos}(\alpha_{12}) & \text{cos}(\alpha_{13})\\\text{cos}(\alpha_{21}) & \text{cos}(\alpha_{22}) & \text{cos}(\alpha_{23})\\\text{cos}(\alpha_{31}) & \text{cos}(\alpha_{32}) & \text{cos}(\alpha_{33})\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\{\mathcal{A}\}\]where \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) is the direction cosine matrix (DCM) or generally referred as rotation matrix. Because each set of basis vectors of \(\mathcal{A}\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) consists of orthogonal unit vectors, the direction cosine matrix \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) is an orthonormal matrix; thus, we have

\[{\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^T = {\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^{-1}\]Hence, the inverse relation from reference frame \(\mathcal{B}\) to \(\mathcal{A}\) is then

\(\{\mathcal{A}\} = {\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{A}}}\{\mathcal{B}\} = {\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^{-1}\{\mathcal{B}\} = {\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^{T}\{\mathcal{B}\}\).

Unlike translation, addition and subtraction of rotations are not summations but rather multiplications. Let’s say we have available the rotation from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{B}\) encoded in \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) and from \(\mathcal{B}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\) encoded in \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}}\). Now the question is: How can I find the rotation from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\) ?

Basically, we have

Rotation \(\mathcal{A} \rightarrow \mathcal{B}\): \(\quad\quad\{\mathcal{B}\} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\{\mathcal{A}\}\)

Rotation \(\mathcal{B} \rightarrow \mathcal{C}\): \(\quad\quad\{\mathcal{C}\} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}}\{\mathcal{B}\}\)

Thus,

Rotation \(\mathcal{A} \rightarrow \mathcal{C}\): \(\quad\quad\{\mathcal{C}\} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}}\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\{\mathcal{A}\} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}}\{\mathcal{A}\}\)

As seen, to accumulate rotations encoded in DCMs or rotation matrices we need to multiply matrices not add them.

Now, using the above relations, we are able to express the set of coordinates (or components) of any vector given in a reference frame into another set of coordinates given in a different reference frame. Let’s express a general vector \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) in reference frames \(\mathcal{A}\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) as

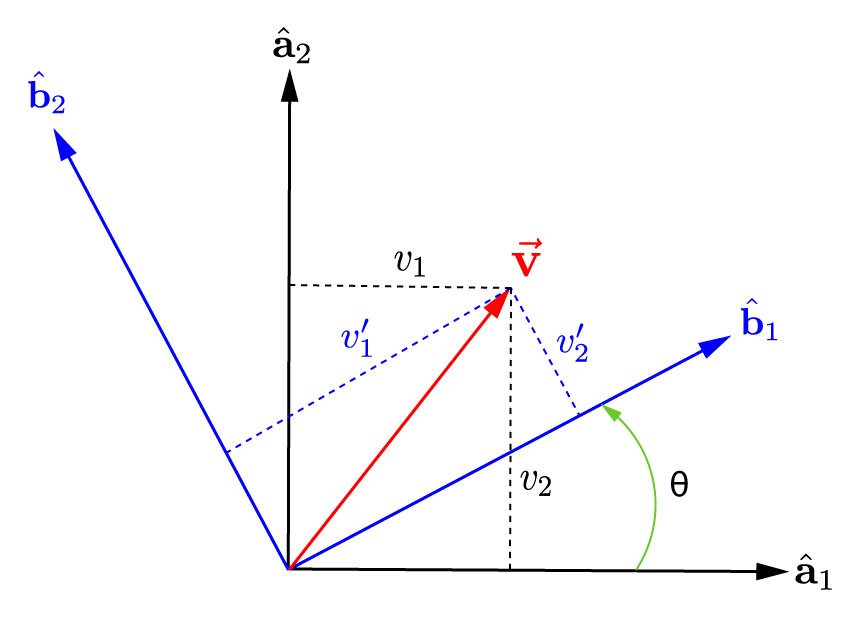

Reference frame \(\mathcal{A}: \vec{\mathbf{v}} = v_1 \hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + v_2 \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + v_3 \hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\)

Reference frame \(\mathcal{B}: \vec{\mathbf{v}} = v_1' \hat{\mathbf{b}}_1 + v_2' \hat{\mathbf{b}}_2 + v_3' \hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\)

Note that \(v_i\) and \(v_i'\) are different coordinates (numbers). Let us project the vector \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) onto the basis vector of the reference frame \(\mathcal{B}\).

\[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\cdot\vec{\mathbf{v}} = v_1' = v_1 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + v_2 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + v_3 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\] \[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_2\cdot\vec{\mathbf{v}} = v_2' = v_1 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_2\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + v_2 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_2\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + v_3 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_2\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\] \[\hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\cdot\vec{\mathbf{v}} = v_3' = v_1 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1 + v_2 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2 + v_3 \hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\]Writing the coordinates in a column matrix and recalling that \(\mathbf{b}_i\cdot\mathbf{a}_j = \text{cos}(\alpha_{ij})\), we can now relate the coordinates of a vector in the reference frame \(\mathcal{A}\) into \(\mathcal{B}\) as

\[\mathbf{v}_{\mathcal{B}} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\mathbf{v}_{\mathcal{A}}\]where \(\mathbf{v}_{\mathcal{B}} = [v_1', v_2', v_3']^T\) and \(\mathbf{v}_{\mathcal{A}} = [v_1, v_2, v_3]^T\). It is important to understand that a vector does not depend on a reference frame, but the coordinates with respect to a reference frame do! Look at figure 2, the vector \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) remains the same, but its coordinates with respect to reference frame \(\mathcal{A}\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) are different.

Animation 1: DCM cosines for different orientations.

Q: Hey Alex! Did you say that you only need three parameters or coordinates to represent the attitude of a reference frame relative to another, right? If so, why do we have 9 coefficients in the DCM?

Yes, you are totally right! However those 9 coefficients are not idependent. Do you remember that the DCM matrix is orthonormal? Let us take a deeper look. So we have \({\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^T = {\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^{-1}\). If we multiply by \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) on both sides, we get

\[{\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^T\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}} = \mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}{\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^T = \mathbf{I}\]where \(\mathbf{I}\) is the identity matrix. So if we equate all the coefficients after performing the matrix multiplication on the right-hand side we get 9 relationhips. Let’s look at the terms on the diagonal. After equating boths sides, we get

\[\text{cos}(\alpha_{11})^2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{12})^2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{13})^2 = 1\] \[\text{cos}(\alpha_{21})^2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{22})^2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{23})^2 = 1\] \[\text{cos}(\alpha_{31})^2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{32})^2 + \text{cos}(\alpha_{33})^2 = 1\]Does these relationships tell you anything? Yes, they are saying something that we did know already. They say that the norm of each basis vector of a reference frame should be 1! Note that the angles \(\alpha_{ij}\) are the projections of the basis vectors of \(\mathcal{B}\) onto \(\mathcal{A}\). Now, any matrix of the form \(\mathbf{A}^T\mathbf{A}\) is called Gram matrix and is always symmetric. This means that \(A_{ij} = A_{ji}\) and of the six off-diagonal relationships, the upper and lower off-diagonal terms are the same. The off-diagonal relationships are

\[\text{cos}(\alpha_{11})\text{cos}(\alpha_{21}) + \text{cos}(\alpha_{12})\text{cos}(\alpha_{22}) + \text{cos}(\alpha_{13})\text{cos}(\alpha_{23}) = 0\] \[\text{cos}(\alpha_{11})\text{cos}(\alpha_{31}) + \text{cos}(\alpha_{12})\text{cos}(\alpha_{32}) + \text{cos}(\alpha_{13})\text{cos}(\alpha_{33}) = 0\] \[\text{cos}(\alpha_{21})\text{cos}(\alpha_{31}) + \text{cos}(\alpha_{22})\text{cos}(\alpha_{32}) + \text{cos}(\alpha_{23})\text{cos}(\alpha_{33}) = 0\]So the number of independent relaionships can only be 6, three equations on the diagonal and three equations on the upper/lower part of \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}{\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^T = \mathbf{I}\). These 6 relationships relate all 9 parameters together (we can express one parameter in terms of the remaining). Thus, the number of “free parameters” is 3 (9 parameters - 6 constraints). Question answered!

Another important property of the DCM is that the determinant is always 1 if the reference frames are right-handed (i.e. they satisfy the right hand rule). Having studiend the main properties of the DCM, we will call \(\mathbf{C}\) the rotation matrix that describes the attitude of \({\mathcal{B}}\) relative to \(\mathcal{A}\) hereafter.

Even though the DCM is a fundamental attitude representation, it may not be the most appropriate one when you want to implement it in real applications. The fact that you carry 9 parameters, instead of only 3, and you need to enforce 6 non-linear constraints every time you update the orientation, that makes the DCM inefficient. So let’s look at alternative representations.

Euler angles

The Euler angles are the most common set of attitude coordinates since they are easy to visualize and interpret. They describe the orientation between two reference frames by using three sequential rotations. Euler angles take advantage of the following statement: “the product of any number of rotation matrices is itself a rotation matrix”. Thus, we can describe the rotation that brings \(\{\mathcal{A}\}\) to \(\{\mathcal{B}\}\) by decomposing it into three sequential “principal” rotations. A principal rotation is described by rotating certain angle \(\theta\) about a principal axis. For example, if we take each basis vector \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\) of reference frame \(\mathcal{A}\) as principal axes, then the principal rotations about those axes yield

\(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\) axis: \(\mathbf{C}_1(\theta) = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 & 0\\0 & \text{cos}(\theta) & \text{sin}(\theta)\\0 & -\text{sin}(\theta) & \text{cos}(\theta)\end{bmatrix}\)

\(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\) axis: \(\mathbf{C}_2(\theta) = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\theta) & 0 & \text{sin}(\theta)\\0 & 1 & 0\\-\text{sin}(\theta) & 0 & \text{cos}(\theta)\end{bmatrix}\)

\(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\) axis: \(\mathbf{C}_3(\theta) = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\theta) & \text{sin}(\theta) & 0\\-\text{sin}(\theta) & \text{cos}(\theta) & 0\\0 & 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\)

Animation 2: Principal yaw, pitch and roll rotations about the principal axes.

Each principal rotation matrix has one parameter or degree of freedom \(\theta\). Since we know that only three degrees of freedom are needed to represent a rotation, a minimum of three principal rotations must be combined sequentially to represent the global rotation that brings \(\{\mathcal{A}\}\) to \(\{\mathcal{B}\}\). This sequence of principal rotations is mathematically expressed as

\[\mathbf{C}(\theta_1, \theta_2, \theta_3) = \mathbf{C}_1(\theta_1)\mathbf{C}_2(\theta_2)\mathbf{C}_3(\theta_3)\]This expression means that we first perform a rotation \(\theta_3\) about the \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\) axis, then a second rotation \(\theta_2\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\) of the new configuration (we have already rotated \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\)), and finally a rotation \(\theta_1\) about the new configuration of \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\). So each \(\mathbf{C}_i(\theta_i)\) is a transformation from a reference frame into another. Let’s break down each rotation

1st rotation \(\mathcal{A} \rightarrow \mathcal{A}'\): rotation of \(\theta_3\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3' = \hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\)

\[\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1'\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2'\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3'\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\theta_3) & \text{sin}(\theta_3) & 0\\-\text{sin}(\theta_3) & \text{cos}(\theta_3) & 0\\0 & 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\end{bmatrix}\]2nd rotation \(\mathcal{A}' \rightarrow \mathcal{A}''\): rotation of \(\theta_2\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2'' = \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2'\)

\[\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1''\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2''\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3''\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\theta_2) & 0 & \text{sin}(\theta_2)\\0 & 1 & 0\\-\text{sin}(\theta_2) & 0 & \text{cos}(\theta_2)\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1'\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2'\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3'\end{bmatrix}\]3rd rotation \(\mathcal{A}'' \rightarrow \mathcal{B}\): rotation of \(\theta_1\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1'' = \hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\)

\[\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{b}}_1\\\hat{\mathbf{b}}_2\\\hat{\mathbf{b}}_3\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 & 0\\0 & \text{cos}(\theta_1) & \text{sin}(\theta_1)\\0 & -\text{sin}(\theta_1) & \text{cos}(\theta_1)\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1''\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2''\\\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3''\end{bmatrix}\]In this case, we use the so called 3-2-1 convention, the most common in aerospace, since we perform a rotation about the \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3'\), \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2''\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1''\) in this order! Note that matrix products are not generally commutative (\(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{B}\neq\mathbf{B}\mathbf{A}\)), so the sequence in which we perform each principal rotation matters. For instance, a convention 3-1-3 or 1-2-3 are different from 3-2-1. In general, there are 12 possible ways to describe the attitude in terms of principal rotations. The angles associated with any of the 12 conventions are called Euler angles and the specific 3-2-1 convention is usually referred as Tait-Bryan angles. In aerospace, the angles of the 3-2-1 convention have a particular name: yaw (\(\psi = \theta_3\)), pitch (\(\theta = \theta_2\)) and roll (\(\phi = \theta_1\)). Does it sound familiar?

If we multiply the three principal rotation matrices, we end up obtaining the rotation matrix parametrized by the Euler angles as

\[\mathbf{C}(\theta_1, \theta_2, \theta_3) = \begin{bmatrix}c_2c_3 & c_2s_3 & -s_2\\s_1s_2c_3 - c_1s_3 & s_1s_2s_3 - c_1c_3 & s_1c_2\\c_1s_2c_3 + s_1s_3 & c_1s_2s_3 - s_1c_3 & c_1c_2\end{bmatrix}\]where \(c_i = \text{cos}(\theta_i)\) and \(s_i = \text{sin}(\theta_i)\).

Inversely, if we want to compute the Euler angles given the rotation matrix we can use

\[\theta_1 = \phi = \text{tan}^{-1}\bigg(\frac{C_{12}}{C_{11}}\bigg);\quad \theta_2 = \theta = \text{tan}^{-1}(C_{13});\quad \theta_3 = \psi = \text{tan}^{-1}\bigg(\frac{C_{23}}{C_{33}}\bigg)\]where \(C_{ij}\) are the entries of the rotation matrix. Note that one must check the sign of \(C_{ij}\) and quadrants for \(\text{tan}^{-1}(\cdot)\). As in the DCM representation, accumulation of rotations using Euler angles are not additive but multiplicative instead. This means that if we have the Euler angles from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{B}\), \(\mathbf{\theta}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}} = \{\psi_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}},\theta_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}}, \phi_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}}\}\), and from \(\mathcal{B}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\), \(\mathbf{\theta}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}} = \{\psi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}},\theta_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}}, \phi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}}\}\), the Euler angles that bring \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\) are not \(\mathbf{\theta}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}} \neq \{\psi_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}} + \psi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}},\theta_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}} + \theta_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}}, \phi_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}} + \phi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}}\}\). To find \(\mathbf{\theta}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}}\) we first need to compute the rotation matrix

\[\mathbf{C}(\psi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{A}},\theta_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{A}}, \phi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{A}}) = \mathbf{C}(\psi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}},\theta_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}}, \phi_{\mathcal{C}\mathcal{B}})\mathbf{C}(\psi_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}},\theta_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}}, \phi_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{A}})\]and then extract the Euler angles \(\mathbf{\theta}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}}\) using the inverse relation presented before.

Q: Wow! So Euler angles are great! We just need to specify \((\theta_1, \theta_2, \theta_3)\) and whalaa! We describe the attitude of \(\mathcal{B}\) relative to \(\mathcal{A}\) in an easy way to visualize and interpret! Why are there more ways to represent the attitude if we already have the Euler angles?

Well…yes Euler angles are great and usually the preferred attitude representation, specially in aerospace! However, there is an important thing to notice. You see that we need to compute three cosines (\(c_1, c_2, c_3\)) and three sines (\(s_1, s_2, s_3\))? Computing trigonometric functions are usually more expensive compared to just direct multiplications and sums. Besides, you always need to make sure about the sequence and convention that represents the attitude. Imagine yur are working with a lot of people on a big project. Every time you receive or deliver a code, you must check and make sure about what convention is being used. Otherwise, a slight confusion may lead to a complete disaster! Finally, there is onle last thing you should care about Euler angles: the so-called gimbal lock.

So, Euler angles make use of three sequential rotations. Let’s see what happens if the second rotation is \(\theta_2 = \frac{\pi}{2}\). In this case, the full rotation matrix reads

\[\mathbf{C}(\theta_1, \frac{\pi}{2}, \theta_3) = \begin{bmatrix}0 & 0 & -1\\\text{sin}(\theta_1 - \theta_3) & \text{cos}(\theta_1 - \theta_3) & 0\\\text{cos}(\theta_1 - \theta_3) & -\text{sin}(\theta_1 - \theta_3) & 0\end{bmatrix}\]The above matrix tells us that if we first rotate \(\theta_3\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\) and then \(\theta_2 = \frac{\pi}{2}\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2'\) we end up with the third rotation axis aligned with \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\). This means that \(\theta_3\) and \(\theta_1\) rotate the reference frame about the same axis! Then, this two rotations about the same axis can be combined in a single rotation \(\theta_{31} = \theta_{1} - \theta_{3}\). That is, \(\mathbf{C}(\theta_1, \frac{\pi}{2}, \theta_3)\) becomes \(\mathbf{C}(\frac{\pi}{2}, \theta_{31})\), we loose one degree of freedom (also known as singularity or locking) and it is no longer possible to get out of it, the attitude is locked. A well-known gimbal lock incident happened in the Apollo 11 Moon mission, where the onboard computer froze the system of gimbals to avoid locking. This singularity appears in all 12 Euler angles conventions at different angles and axes; however, the 3-2-1 convention minimizes this effect by widening the angluar range, thus allowing more attitude representations before locking happens.

Animation 3:Left: 3-2-1 sequence of Euler angles. Right: Gimbal lock phenomenon. The first and third rotations are performed about the same axis.

Let’s move on!

Axis-angle representation

The axis angle representation defines the relative attitude of two reference frames by means of a rotation \(\Phi\) (angle) about a unit vector \(\hat{\mathbf{e}}\) (axis).

According to Euler:

A rigid body or coordinate reference frame can be brought from an arbitrary initial orientation to an arbitrary final orientation by a single rigid rotation through a principal angle \(\Phi\) about the principal axis \(\hat{\mathbf{e}}\); the principal axis is a judicious axis fixed in both the initial and final orientation.

Q: Okay,okay sounds good…but can you translate that into English?

Sure, let’s start! In plain English that means that the principle axis (vector) has the same coordinates in two different reference frames. So, using the coordinate transformation matrix from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{B}\), the above statement can be mathematically expressed as

\[\begin{bmatrix}e_1\\e_2\\e_3\end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{C}\begin{bmatrix}e_1\\e_2\\e_3\end{bmatrix}\]Have you ever seen a similar expression before? What if I write it like this…

\[\mathbf{C}\mathbf{e} = \lambda \mathbf{e}\]Yes! This is the ubiquitous eigen-decomposition equation. Basically, Euler’s theorem states that the principal axis that relates two reference frames is an eigenvector of the rotation matrix relating those frames with eigenvalue \(\lambda = 1\).

Again we have redundancy in the parameters needed to describe the attitude of an object: three components of \(\hat{\mathbf{e}}\) and \(\Phi\). In this case, the constraint that reduces the degrees of freedom down to three is that the principal axis must have unit norm \(\|\hat{\mathbf{e}}\|_2 = e_1^2 + e_2^2 + e_3^2 = 1\). Inspecting the axis-angle representation a little further, you will notice that \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi)\) and \((-\hat{\mathbf{e}},-\Phi)\) represents the same orientation. Moreover, given the same axis, we can describe the same orientation taking the shortest or the longest path. For example, if the shortest path is \(\Phi = 30^{\circ}\), the longest one is then \(\Phi' = 30^{\circ} - 360^{\circ} = -330^{\circ}\). Both paths differ by \(360^{\circ}\). Thus, we have four possible combinations to describe the same attitude: \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi)\), \((-\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi)\), \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi - 2\pi)\), \((-\hat{\mathbf{e}},-\Phi + 2\pi)\). In most cases \(\Phi\) is simply chosen to be \(-\pi\leq \Phi\leq \pi\).

Animation 4:Left: Axis-angle representation for different orientations. Right: Long and short paths for the same axis. Boths paths reach the same attitude.

After some algebra, it can be shown that the rotation matrix associated with the axis-angle coordinates is given by

\[\mathbf{C}(\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi) = \text{cos}(\Phi)\mathbf{I} + (1-\text{cos}(\Phi))\mathbf{e}\mathbf{e}^T - \text{sin}(\Phi)\mathbf{e}^{\times}\]where

\[\mathbf{e}\mathbf{e}^T = \begin{bmatrix}e_1 e_1 & e_1 e_2 & e_1 e_3\\ e_2 e_1 & e_2 e_2 & e_2 e_3\\ e_3 e_1 & e_3 e_2 & e_3 e_3 \end{bmatrix};\quad\mathbf{e}^{\times} = \begin{bmatrix}0 & -e_3 & e_2\\ e_3 & 0 & -e_1\\ -e_2 & e_1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\]Contrarily, the inverse relation can yields

\[\Phi = \frac{1}{2}(C_{11} + C_{22} + C_{33} -1);\quad \mathbf{e} = \frac{1}{2 \text{sin}(\Phi)}\begin{bmatrix} C_{23} - C_{32}\\C_{31} - C_{13}\\C_{12} - C_{21}\end{bmatrix}\]Q: Awww… too many numbers and equations! So, the Euler angles contain singularities called locking. Do the axis-angle representation have singularities too?

Yes… this topic is not the most easy to digest, I agree. Right, the axis-angle representation is not exempt from singularities. However, the singularity is mild compared to Euler angles. In the axis-angle representation the singularity appears at the zero rotation \(\Phi = 0\), when the \(\hat{\mathbf{e}}\) axis is not defined.

One of the reasons axis-angle parameters are not as appealing as other attitude representations is because the math involved when dealing with succesive rotations is intrincate and not the most suitable for computer implementation. However, the axis-angle representation is fundamental to understand the last attitude description I am going to discuss… Can you guess which one is it?

Quaternions

And finally, quaternions! One of the most powerful and convenient ways to describe orientations.

Q: Woah! quat..what? that sounds a bit scary and math intense!

Well, yeah sort of… I am not going to discuss in detail the math involved…I will rather give a more digestible explanation. Quaternions are not the most intuitive and easy to visualize to be honest, but very useful, computationally efficient and most importantly, free of singularities!

Quaternions are a three-dimensional extension of complex numbers. Do you remember from calculus that \(z = x + yi\), where x and y are the real and imaginary components respectively, defines a complex number? So quaternions extend this definition and add two more components for the imaginary domain \(q = q_0 + q_1i + q_2j + q_3k\) with the following property \(i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = ijk = -1\). Quaternions were first proposed by William Rowan Hamilton in 1843 as an extension of the complex numbers. However, here we will focus on attitude quaternions to represent rotations.

Similar to the close relationship between DCM and Euler angles, the quaternions are closely related to the axis-angle representation. The components of the quaternion can be expressed in terms of the axis-angle parameters through

\[q_0 = \text{cos}\big(\frac{\Phi}{2}\big);\quad q_1 = e_1 \text{sin}\big(\frac{\Phi}{2}\big);\quad q_2 = e_2 \text{sin}\big(\frac{\Phi}{2}\big);\quad q_3 = e_3 \text{sin}\big(\frac{\Phi}{2}\big)\]For convenience, a quaternion can be expressed as a four-component column matrix

\[\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}} = \begin{bmatrix}q_0\\q_1\\q_2\\q_3\end{bmatrix}\]Just to warn you, we are using the convention that the \(q_0\) component is located at the first entry of the quaternion matrix. However, some other people locate it at the fourth entry. This slight difference makes the operations involving quaternions a bit different and one must carefuly check what convention is being used. We will drop the sub and superscripts \(\mathcal{A}\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) to make the notation easier to read, but never forget that any attitude representation relates two reference frames!

Again, we have a redundant parameter since we only need three to describe orientations. However, since \(\hat{\mathbf{e}}\) must be unit-norm, the constraint on the quaternion components is then

\[||\mathbf{q}||_2 = q_0^2 + q_1^2 + q_2^2 + q_3^2 = 1\]Have you seen a similar expression before? Does \(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = r^2\) look familiar to you? Yes! The components of the quaternion must lie in a sphere of radius one. However, this time the sphere lives in a four-dimensional space, called hypersphere.

Q: Well…I knew that was coming…more math! So, how can one visualize how these components relate to rotations?

Let’s try to break down how the components relate to fundamental rotations about the axes of a reference frame. So, imagine we want to rotate \(60^{\circ}\) about the \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1\) axis of reference frame \(\mathcal{A}\). The components of that axis in \(\mathcal{A}\) are \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_{1 \mathcal{A}} = [1,0,0]^T\). The quaternion associated with that rotation is then

\[\mathbf{q} = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\frac{\pi}{3}/2)\\1*\text{sin}(\frac{\pi}{3}/2)\\0*\text{sin}(\frac{\pi}{3}/2)\\0*\text{sin}(\frac{\pi}{3}/2)\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\\\frac{1}{2}\\0\\0 \end{bmatrix}\]If we want to rotate \(60^{\circ}\) about \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_2\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_3\), the quaternions associated with these rotations are respectively

\[\mathbf{q} = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\\0\\\frac{1}{2}\\0 \end{bmatrix}\quad\text{and}\quad\mathbf{q} = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\\0\\0\\\frac{1}{2}\end{bmatrix}\]Unlike the axis-angle representation, the zero rotation is defined by the quaternion identity \(\mathbf{I}_q = [1, 0, 0, 0]^T\). If you check out all these quaternion examples, you will see that they all have unit norm. That is the main difference between general quaternions and attitude quaternions.

Given a certain attitude, there are actually two quaternions representing the same orientation. This is due to the non-uniqueness of the axis-angle representation. On the one hand, the sets \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi)\) and \((-\hat{\mathbf{e}},-\Phi)\) represent the same quaternion \(\mathbf{q}\). On the other hand, \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi - 2\pi)\) will give

\[\mathbf{q}' = \begin{bmatrix}\text{cos}(\frac{\Phi}{2} - \pi)\\e_1\text{sin}(\frac{\Phi}{2} - \pi)\\e_2\text{sin}(\frac{\Phi}{2} - \pi)\\e_3\text{sin}(\frac{\Phi}{2} - \pi)\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}-\text{cos}(\frac{\Phi}{2})\\-e_1\text{sin}(\frac{\Phi}{2})\\-e_2\text{sin}(\frac{\Phi}{2})\\-e_3\text{sin}(\frac{\Phi}{2})\end{bmatrix} = -\mathbf{q}\]but since \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi - 2\pi)\) is the same attitude as \((\hat{\mathbf{e}},\Phi)\), then \(\mathbf{q}' = -\mathbf{q}\) should describe the same orientation as \(\mathbf{q}\). Again, this redundancy is related to the fact that there are two paths to reach the same attitude, the short and long ones. We saw that the shortest path is given by \(-\pi \leq \Phi\leq \pi\), so \(\frac{\Phi}{2}\) must live in the first and fourth quadrants. This means that restricting the first component of \(\mathbf{q}\) to be \(q_0 \geq 0\) will yield the orientation with the shortest path.

Animation 5:Left: Quaternion representation for different orientations. Right: Long and short paths that reach the same attitude.

The rotation matrix can be expressed in terms of quaternions as

\[\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{q}) = \begin{bmatrix}q_0^2 + q_1^2 - q_2^2 - q_3^2 & 2(q_1 q_2 + q_0 q_3) & 2(q_1 q_3 - q_0 q_2)\\ 2(q_1 q_2 - q_0 q_3) & q_0^2 - q_1^2 + q_2^2 - q_3^2& 2(q_2q_3 + q_0q_1)\\ 2(q_1q_3 + q_0q_2) & 2(q_2q_3 - q_0q_1) & q_0^2 - q_1^2 - q_2^2 + q_3^2 \end{bmatrix}\]The inverse relation from rotation matrix to quaternion representation can be found by inspection of the above relationship. However, the direct relationship may not be computationally robust. This means small errors on the \(C_{ij}\) coefficients may be amplified on the quaternion components. There are more robust ways to compute quaternions from rotation matrices, for example the commonly used Shepperd’s method.

Now, we are interested in finding the rotation from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\) that results from two consecutive rotations \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{B}\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\). How do we do that?

Q: Well since quaternions are related to DCM’s, given the attitude quaternions we can express the rotations \(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) and \(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}}\) in terms of DCM, multiply the DCM’s resulting in \(\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}}) = \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}}) \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}})\) and use Shepperd’s method to obtain \(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}}\). Right?

Wooow, you learn fast! You are absolutely right! However, this approach involves many operations, may be computationally inefficient and you may loose accuracy… A better approach would be to use quaternion multiplication directly. Do you remember that quaternions are extensions of complex numbers? So we can multiply quaternions and use the rule \(i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = ijk = -1\) to obtain the resulting product

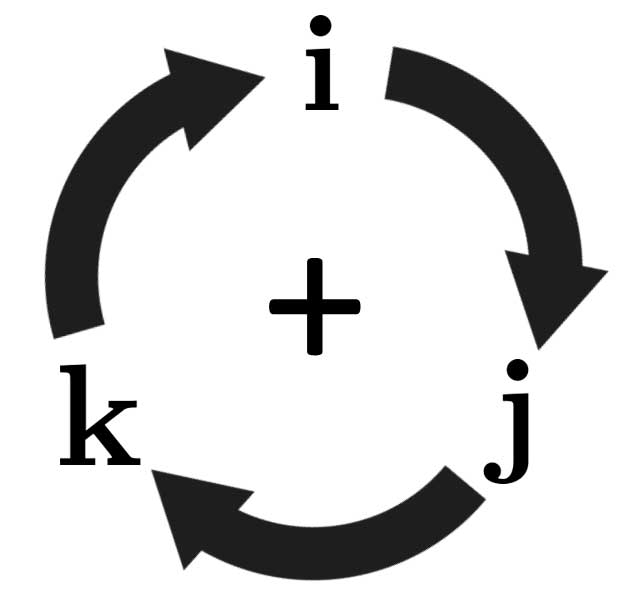

\[q p = (q_0 + q_1i+ q_2j+ q_3k)(p_0 + p_1i + p_2j + p_3k)\]The quaternion multiplication represents a cyclic permutation on \(i, j, k\), this means that

\[ij = k,\quad jk = i,\quad ki = j,\quad ik = -j,\quad kj = -i,\quad ji = -k\]Q: Mmmm…okay…that is complicated to remember…

Do not worry! I have a way to remember all these rules using a simple diagram. In fact, I used it when I was writing this post.

This diagram means that multiplying two consecutive components clockwise will result in the third one. In contrast, if we multiply two components counterclockwise will give the negative of the following component. As you can see, the direction in which we multiply the components matter. This means that quaternion multiplication is not commutative \(qp \neq pq\). Do you recall we said that rotations are not commutative? So, attitude quaternions must also satisfy this property. For computations, quaternion multiplication is conveniently expressed as a matrix multiplication. So the quaternion from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\mathcal{C}\) is simply

\[\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{C}} = \mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}} \otimes \mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}} = \begin{bmatrix} p_0 & -p_1 & -p_2 & -p_3\\q_1 & p_0 & p_3 & -p_2\\p_2 & -p_3 & p_0 & p_1\\p_3 & p_2 & -p_1 & p_0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} q_0\\q_1\\q_2\\q_3\end{bmatrix}\]where \(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}} = [q_0, q_1, q_2, q_3]^T\) and \(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}} = [p_0, p_1, p_2, p_3]^T\) and \(\otimes\) denotes quaternion multiplication. Like the location of the \(q_0\) component, there are several conventions for quaternion multiplication. I defined the quaternion multiplication \(\otimes\) as the above matrix-vector product in that specific order to be consistent with the addition of rotations using DCM, where you start with the first rotation to the right and keep adding subsequent rotations to the left. However, using the hypercomplex number form and calling \(q\leftarrow \mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) and \(p\leftarrow\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{C}}\), the above expression corresponds to \(qp\), not \(pq\). So, care must be taken to thoroughly understand the conventions embodied in any quaternion equation that one chooses to reference!

Q: It looks really confusing…I will make sure to double check the convention everytime I use quaternions! One question, so for DCM I recall that given \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}\) you just transpose the matrix to obtain the inverse relation \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{A}} = {\mathbf{C}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^T\), right? How does that work for quaternions?

You are right and that is a good question! So, for matrices there exist the inverse matrix such that \(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{A}^{-1} = \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{I}\), right? And in the case the matrix is orthogonal \(\mathbf{A}^{-1} = \mathbf{A}^T\). For quaternions, it also exists the inverse quaternion \(\mathbf{q}^{-1}\) such that \(\mathbf{q}\otimes\mathbf{q}^{-1} = \mathbf{q}^{-1}\otimes\mathbf{q} = \mathbf{I}_q\). Much like matrices, an important property is \((\mathbf{p}\otimes\mathbf{q})^{-1} = \mathbf{q}^{-1}\otimes\mathbf{p}^{-1}\). It turns out that the inverse quaternon is its conjugate divided by its norm

\[\mathbf{q}^{-1} = \frac{\mathbf{q}^{\ast}}{\lVert\mathbf{q}\rVert_2}\]where the conjugate, similar to complex numbers, is defined as \(\mathbf{q}^{\ast} = [q_0, -q_1, -q_2, -q_3]^T\). We know that for attitude quaternions \(\lVert\mathbf{q}\rVert_2 = 1\). However, for computational purposes and roundoff errors, we keep division by the norm to enforce unitary quaternions. Therefore, like DCM’s, the attitude quaternion from \(\mathcal{B}\) to \(\mathcal{A}\) is then \(\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{B}}^{\mathcal{A}} = {\mathbf{q}_{\mathcal{A}}^{\mathcal{B}}}^{\ast}\) (assuming exact unit norm).

And…I think that is enough! Of course, there are entire books on this topic and a lot more to learn! I tried to compact all the relevant information to understand the fundamentals of orientations in three-dimensional space. I had so much fun writing this post. My goal was to make complicated concepts easier to understand through dialogues and cool animations rather than focusing on math. If you are interested in any of the figures or animations of this post, I will be happy to share the files and codes.

I hope you enjoyed this post! Thank you so much for reading!

Alex.

References

1) Hughes, Peter C. Spacecraft attitude dynamics. Courier Corporation, 2012.

2) Markley, F. Landis, and John L. Crassidis. Fundamentals of spacecraft attitude determination and control. Vol. 33. New York: Springer, 2014.

3) Junkins, John L., and Hanspeter Schaub. Analytical mechanics of space systems. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2009.

4) Wie, Bong. Space vehicle dynamics and control. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2008.

5) Coursera. Course: Spacecraft Dynamics and Control by Prof. Hanspeter Schaub (University of Colorado Boulder). Link: https://www.coursera.org/specializations/spacecraft-dynamics-control#courses. Highly recommended!