Space-based observations have transformed our understanding of Earth, the solar system and the universe we live in. During the past decades, driven by our need of exploration and answering increasingly complicated questions, space observations have become more sophisticated and costly, in the order of billion of dollars. Gathering data from satellites has been crucial not only for scientific research, but also for companies and businesses interested in extracting important information for their internal operations. Although sophisticated missions requiring large and heavy spacecraft will continue in the future, small satellites with affordable costs are gaining popularity among research centers and companies as an alternative to answer scientific questions and providing relevant data in a rapid, more affordable manner.

CubeSat? What is that?

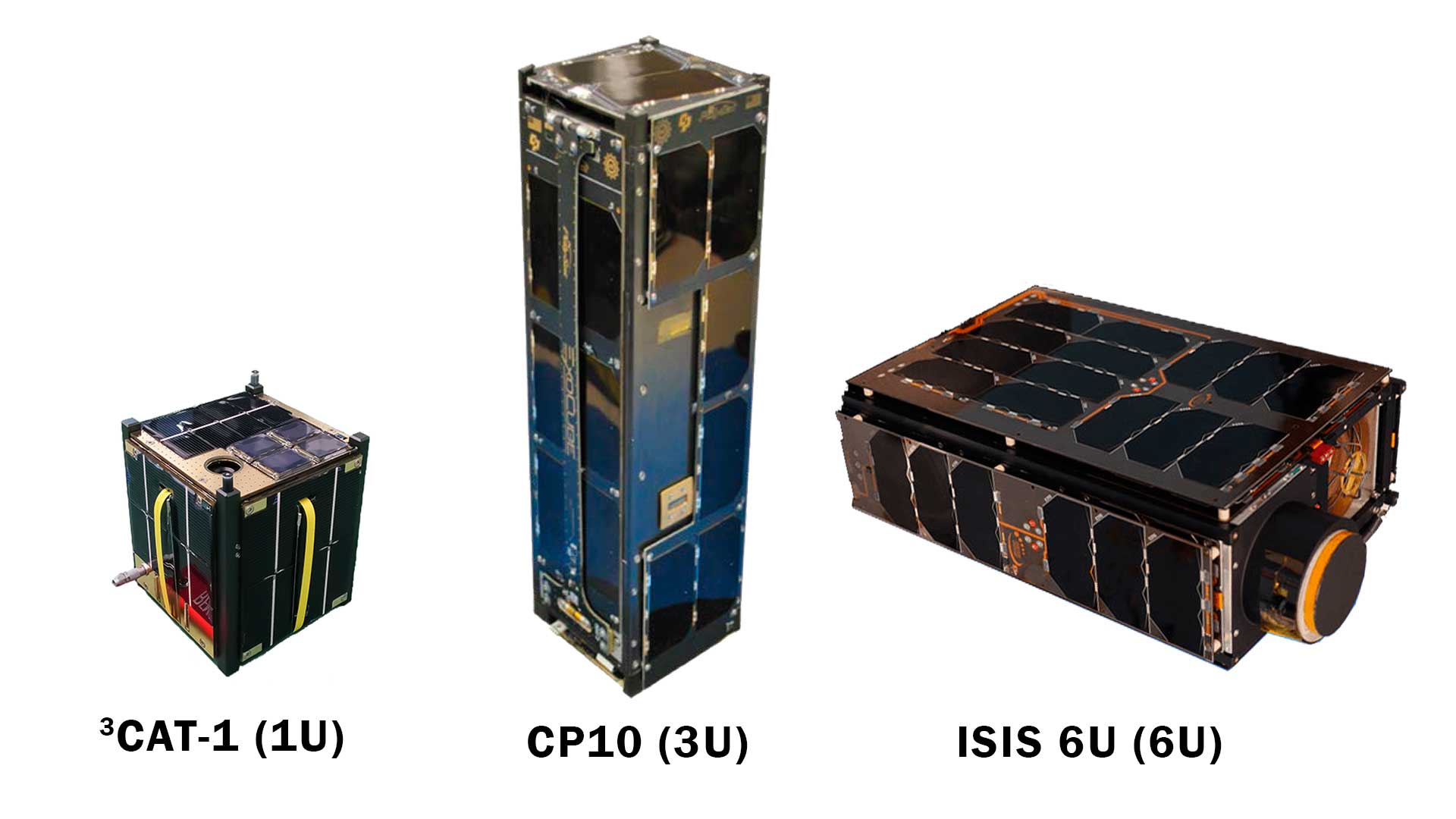

CubeSats are types of miniaturized satellites that use a standardized sizes and shapes. They are made up of multiples of 10cm x 10cm x 10cm cubic units, referred as “1U”, with a mass no more than 1.33 kg (2.9 lbs) per unit, and often use commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their subsystems. Although the base unit is a 1000cm^3 cube, Cubesats are extendable to larger sizes ranging from 0.25U to 27U (see figure 1). As a result, the engineering and development of CubeSats becomes less costly than other highly customized satellites. Their small size and light weight also reduce costs associated with transporting them to, and deploying them into, space.

Cubesats are usually put into Low-Earth Orbit (LEO), Earth-centered orbits with an altitude of less than 2000km (1200 mi), and commonly deployed from the International Space Station (ISS) or from launch vehicles as secondary payloads. Originally, Cubesats were dispensed by a standardized deployment system called P-POD (Poly-Picosatellite Orbit Deployer) to ensure all developers to conform to common physical requirements. The P-POD minimizes potential interactions with primary payloads by enclosing Cubesats in a tubular structure.

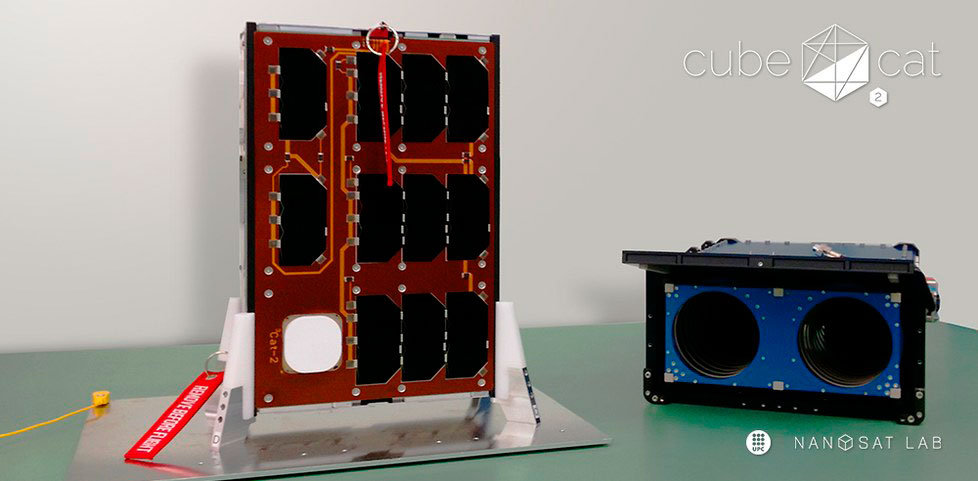

As an example, figure 2 on the left, shows the 3Cat-2 nanosatellite developed developed by the Nanosat lab of the Polytechnic University of Catalonia back in 2016. The aim of the 3Cat-2 mission was to test dual frequency GNSS-R altimeter for Earth Observation and validate two in-house magnetometer and star-tracker devices. 3Cat-2 belongs to the 6U class of Cubesats, consisting of 6 1U modules arranged in a 3 x 2 grid structure with dimensions 100 mm x 243.7 mm x 340.5mm and total weight of 7.1 kg (15.7 lbs). On the right of figure 2, we can see the P-POD used to deploy the spacecraft from the launch vehicle.

Figure 3 shows an exploded view of 3Cat-2 with each of its 1U modules. Three of the modules were used as payload, equipped with all the instrumentation to perform the tests and experiments. The remaining modules were intended for controlling the spacecraft, generating and distributing electric power and running the on-board software. The top panel consisted of six planar antennas for communications.

3Cat-2 was successfully put into a polar, 400 km Low-Earth Orbit by the Chinese Long March 2D launch vehicle in May 2016.

What is the cost to develop and launch a Cubesat? How long does the whole process take?

Developing Cubesats according to CubeSat standards contributes to cutting costs during the design and integration phases. Their small size and light weight also reduce the expenses of transportation and deployment. The total amount for developing a CubeSat, excluding launch, depends on the type of the mission, on-board instrumentation, size and weight… As a reference, the average cost to build a commercial Cubesat is $100,000 per unit.

Then, one needs to add the launch expenses, which depend on the type of orbit, carrier and whether it is a dedicated or a rideshare launch. Nowadays, there are many companies offering launch services for modest prices. The list below provides some rideshare launch costs from different providers:

- ISIS Space (EU): $210,000 – 270,000 for 3U LEO

- Rocket Lab (NZ): $70,000- 80,000 for 1U LEO and $200,000- 250,000 for 3U LEO

- SpaceFlight (USA): $295,000 for 3U LEO and $545,000 for 6U LEO

- SpaceX (USA): $1M for LEO small sat up to 200 kg

- Nanoracks (USA): $85,000 for 1U LEO

According to the above numbers, the average price to place a Cubesat in LEO orbit is less than $100,000 per unit, making the overall cost to develop and launch a Cubesat around $200,000 per unit. For comparison, the average cost to build and launch a large commercial spacecraft is around $300 M.

Apart from the reduced cost, the biggest advantage of Cubesats is the short time period to develop each model. The standards and specific requirements allow the manufacturer to start the development with reference values in mind and accelerate the design, integration and testing phases. The required time can take from six months to two years depending on the application, as compared to conventional satellites that require five to fifteen years.

Cubesat applications: small size, but great potential

Cubesats represent a new paradigm in the satellite industry. Their small size and low-cost do not prevent them from carrying out the same tasks as their bigger brothers . Of course, their features differ, but are sufficient for a wide range of scientific and industrial applications. Some of the most important CubeSat applications are listed below:

1. Education and technology demonstrators

Cubesats are cost-effective platforms to provide students with spacecraft design training and to test new technology at a much lower risk.

2. Scientific applications

In addition to commercial applications, Cubesats can be used for space exploration, interplanetary missions, system testing in orbit or material and biomedical research under microgravity conditions.

3. Earth Observation

Collecting and interpreting data is essential for the management of natural resources and developing sustainable technologies. Analyzing human impact on agriculture, forest, geology and the environment is crucial to improve societies living conditions.

4. Communications and Internet of Things

Nanosatellites have laid the foundations for developing the Internet of Things (IoT) on a global scale, connecting areas of the world without land communication cover via infrastructures in space. There is a growing number of sensorised objects and networks requiring global connections and communications.

5. Geolocation and Logistics

Locating and handling assets (aircraft, ships, vehicles, etc.) can prove impossible or at best extremely costly in areas where there is no land cover. Located in space and offering a global vision, nanosatellite constellations can provide immediate monitoring of various asset groups anywhere on the planet. Nanosatellites can complement current networks by providing complex logistic management solutions.

6. Signal Monitoring

Nanosatellites can monitor radio signals transmitted from Earth. This means that in the event of a disaster, they can provide initial information regarding the degree of impact and the most seriously affected areas, allowing for more effective planning of rescue and relief work.

From 1999 to 2020: The evolution of CubeSats in the last 20 years

The CubeSat concept and program were originally developed in 1999 as a collaborative effort between Professors Jordi Puig-Suari, at California Polytechnic State University, and Bob Twiggs, at Stanford University to provide an affordable platform for the academic community to access space. In early 2000’s, Cubesats were regarded as “toy” satellites to provide students with training in the design, integration, test and operation of real spacecraft and enable researchers to perform space science and exploration. Cubesats were not initially set out to become a standard; rather, standards and specifications were developed over time as nanosatellites gained interest by the research community.

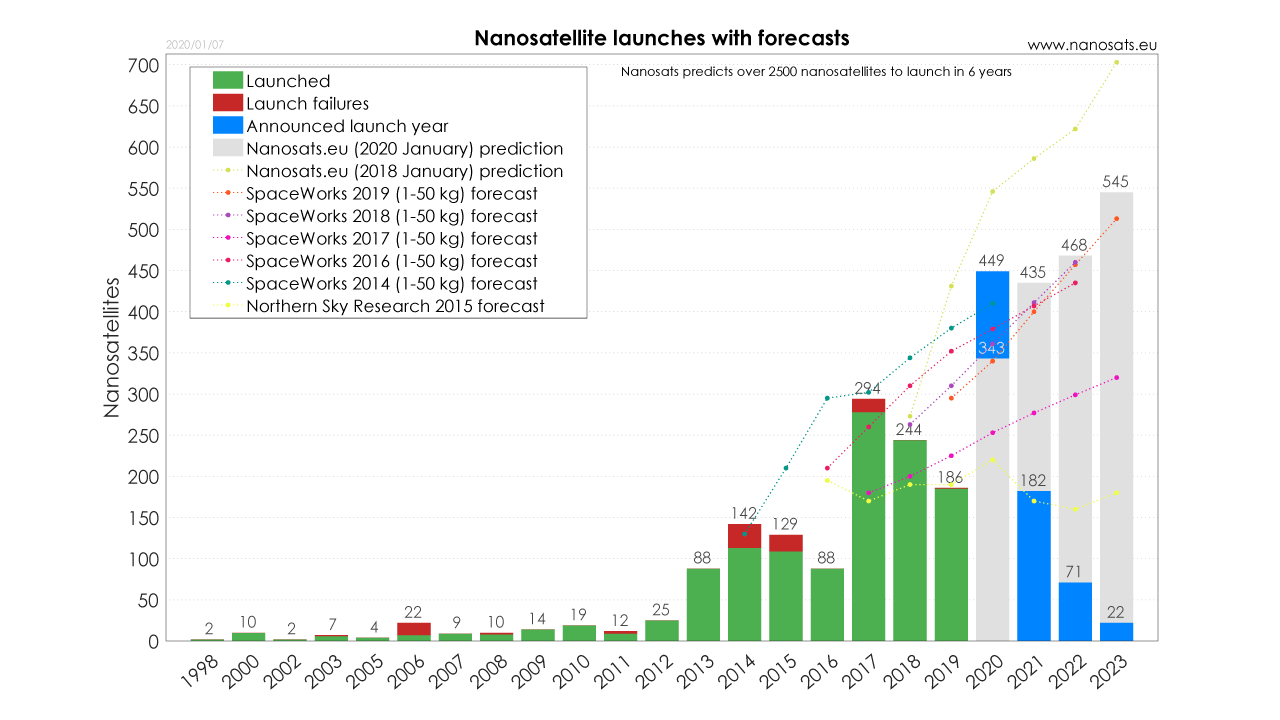

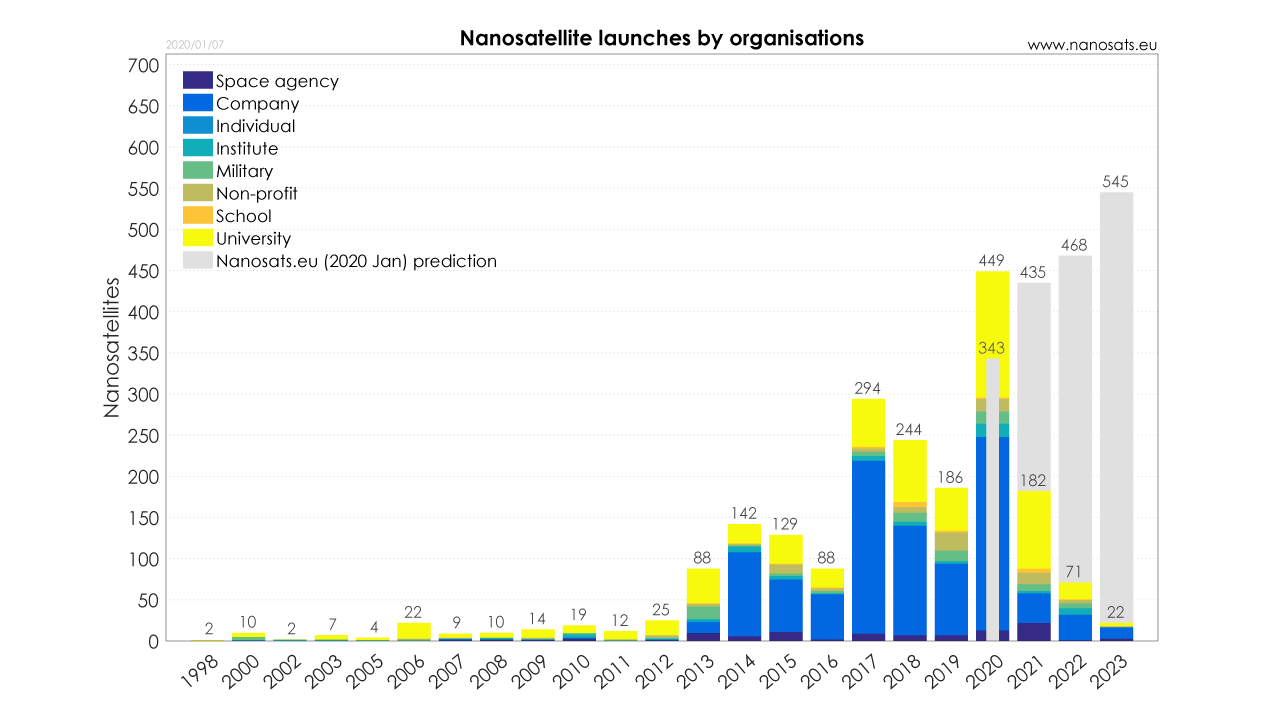

The first six Cubesats were launched in June 2003 abroad a Russian Rockot launch vehicle, with three more CubeSats aboard a Kosmos-3M rocket in 2005. During that time, Cubesat technology development began within universities, government agencies, and industry. In 2008, university-led programs made up 75% of all Cubesats launched. After 2010, new commercial players were emerging as technology providers and also as companies developing and launching entire CubeSat systems, mostly for Earth observation and communication applications. By the end of 2012, 112 CubeSat-class missions were flown, fielded by nearly 80 organizations from 24 countries on 29 rockets, representing universities, government agencies, private companies, and amateur organizations. In 2016, a record of satellites launched by a single rocket was established by PSLV, with 101 CubeSats launched at once along with 3 other satellites. Starting in 2018, CubeSats began to venture outside of Earth orbit. The first interplanetary CubeSats, the twin MarCO-A and MarCO-B, were launched in May 2018 alongside NASA’s InSight lander on their way to Mars. As of January, 2020, 1200 CubeSats have been put into orbit by 65 countries. Figure 6 shows the evolution of nanosatellite launches from 1999 to 2020 and a forecast until 2023.

As shown in figure 6, CubeSats begun as technology demonstrators among universities. The success of early missions encouraged industry and startup companies to adopt these tiny satellites for their services and operations.

What are the future perspectives?

CubeSats are now commonly used in low Earth orbit for applications such as remote sensing and communications. Companies such as Planet Labs or Tyvak Aerospace offer access to their CubeSat fleet for monitoring, visualization, tracking or communications to name a few of their services. As we advance to a further democratization of space and Cubesat technology becomes well established and more reliable, seamless global coverage and interconnectivity seems increasingly appealing for industry. CubeSat constellations are envisioned to enable next generation wireless networks in space such as 5G connectivity and permit novel infrastructure solutions to bring IoT out of home. Recent startups, such as Swarm Technologies, Astrocast or Lacuna Space, are betting high on nanosatellites for IoT applications.

The potential of these tiny satellites seems to have no limits. CubeSats are beginning to venture farther afield and are certainly changing the game when it comes to space exploration. The success of the MarCO mission set a reference to interplanetary missions using low-cost spacecraft. “Getting into deep space like we did shows that this is only the beginning for CubeSat missions to explore the solar system […] We’ve put a stake in the ground. Future CubeSats might go even farther.” said MarCO chief engineer Andrew Klesh.

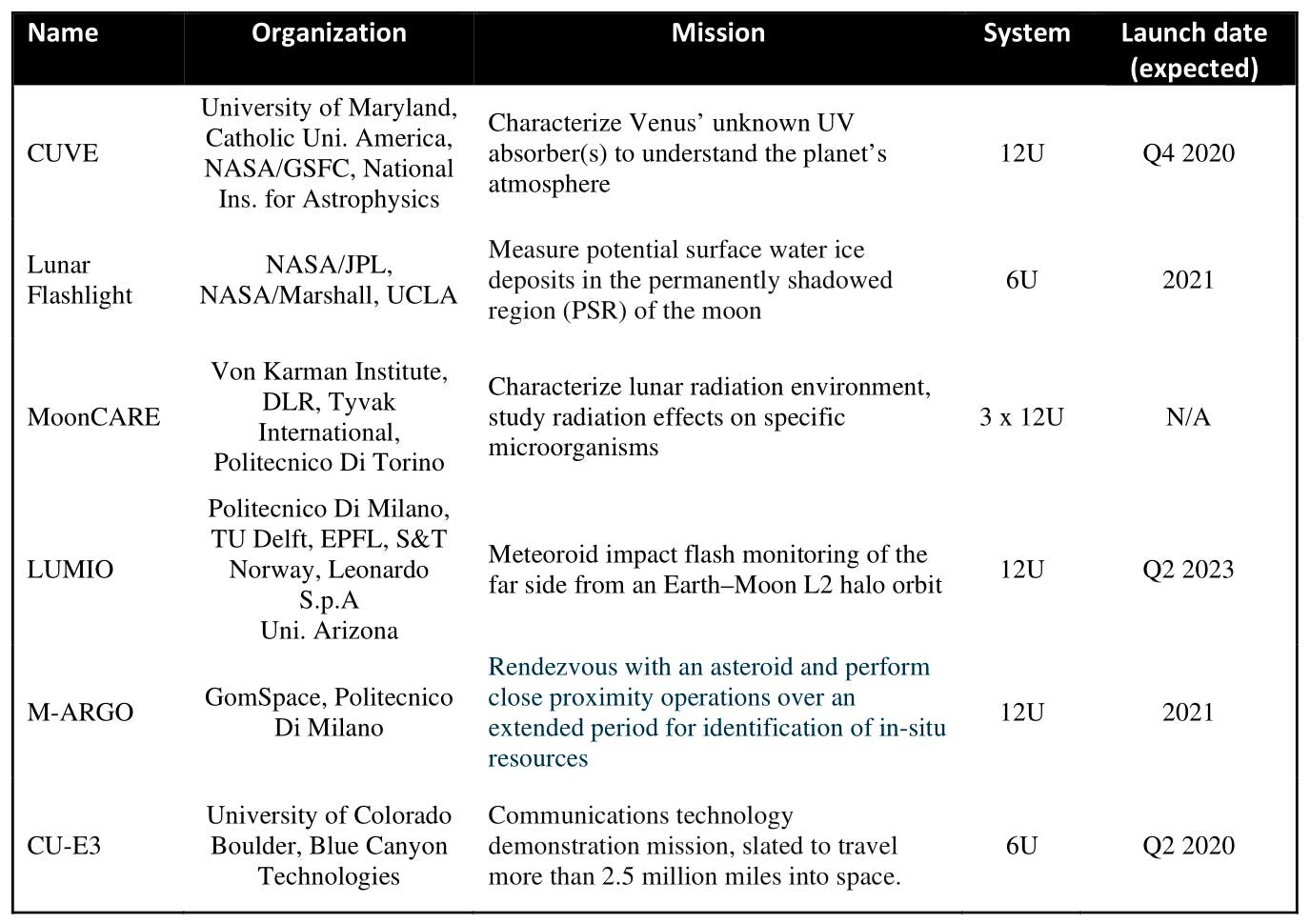

Exploration of deep space marks the next giant leap for nanosatellites. There are ambitious missions afoot to explore the Moon, Mars and near-Earth asteroids using CubeSats. These plans are led not just by government-space agencies but include university research groups, research laboratories and startups. Table 1 illustrates some of the upcoming deep space CubeSat missions.

Affordable nanosatellites are also a kind of gateway technology for those looking to get involved in space exploration. Nations including Colombia, Poland, Estonia, Hungary, Romania and Pakistan have begun their own space programs by hitching a ride with a CubeSat. The Japanese Space Agency has collaborated with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) to set up KiboCUBE, a project that offers developing countries the opportunity to deploy their own CubeSats from the ISS. This opens the possibility of future international cooperation and knowledge transfer, boosting the aerospace sector.

More small spacecraft are on the way and it seems they will revolutionize the aerospace sector as a low-cost, faster alternative to access space. National Aerospace Agencies, Universities, research Laboratories and startup companies are set to launch a variety of new CubeSats in coming years. The future of these tiny satellites is promising and only time will tell how far they can go.

References

2) NASA Science, 10 Things: CubeSats — Going Farther

5) Deep-space CubeSats: thinking inside the box (article by Roger Walker)

7) Towards the Thousandth CubeSat: A Statistical Overview

8) Wikipedia article about Cubesats